I just have a new paper out in Journal of Health Economics. It’s about emergency departments (EDs) and the different patients they treat. It’s free to read here: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2024.102881. This is a summary that expands slightly on the Twitter/X thread (here).

Crowding (and very long waits that come with it) is a problem as it may have detrimental effects on quantity and quality of care, and even adverse health effects for patients. There’s literature on that.

Crowding is mainly a resource constraint problem. EDs may receive too many patients for the amount of resources (staff, rooms, …) that they are prepared to take.

Avoidable emergency department (ED) visits have been partially blamed for the growing crowding of EDs, in England and elsewhere. Policies (and a lot of money to implement them) have been trying to divert demand from avoidable patients demand away from EDs, often towards primary care settings. This assumes that they are substantially adding to the problem.

We ask whether demand from “avoidable” patients causes disruptions to care and outcomes of so-called “non-avoidable” patients, i.e. the urgent patients that EDs are meant to treat. Or: are binding resource constraints the most likely cause of crowding-related issues?

The idea is that if EDs triage patients effectively, avoidable patients will be assigned lower priority without harming urgent patients. Waiting times will work as rationing mechanism, and the less urgent among the non-urgent will simply leave.

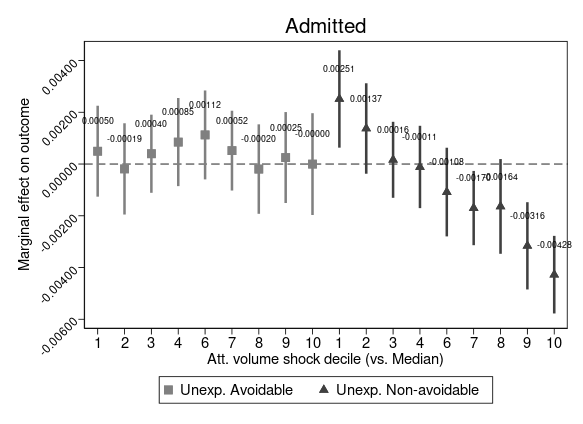

We find evidence confirming these hypotheses. Unexpected demand from avoidable patients causes little to no disruption to the care received by urgent patients, and sensibly less than disruption caused by unexpected demand from non-avoidable patients. The following figure shows a good example, where unexpected avoidable attendances aren’t changing the probability of being admitted of urgent patients. Not necessarily surpising I guess, but important to also verify empirically.

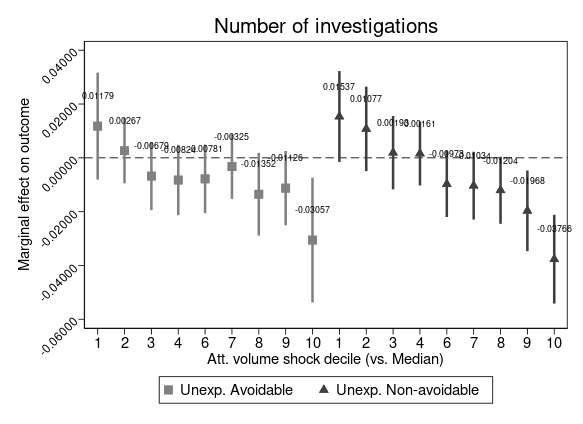

How about treatment intensity? “Too many” patients unexpectedly showing up at the ED decrease the number of investigations delivered to urgent patients, no matter if these unexpected attendances are avoidable or not. But: this happens only at very high levels of unexpected demand and the impact of additional avoiable patients is substantially milder.

Why unexpected volumes? Because not all changes in demand are alike. There are seasonal pattern that EDs prepare for. Attendances on different days are also different (think about a Sun vs. a Wed). Focusing on plausibly exogenous demand shifts allows to isolate “true” responses. We expand on the empirical approach in the paper (+ have a ton of robustness checks): check it out if interested.

This work builds on previous brilliant work by Alex Turner (mainly this) and Beth Parkinson (mainly this). We tried to add to the literature by unpacking demand heterogeneity, by patient type and across distribution of unexpected demand.

Findings may help in the debate around avoidable visits. They seem very hard to divert away from EDs (see, for example, this). Some may even say that they shouldn’t be diverted away, in a world where primary care is under immense pressure. So maybe upping capacity of EDs is the only way? But at what cost? Would that be cost-effective?

Shout-out to Reviewers and Editor, all conference participants who gave great feeback (HESG and others), and funders NIHR ARC Greater Manchester and MRC.